10-12 November 2017

Over the past three years I’ve scouted out and published many Science Fiction stories from around the world. Through the independent small press Future Fiction, I’ve published more than 60 stories translated from English, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Chinese. China has been particularly striking in recent years, with two authors – Liu Cixin (刘慈欣) and Hao Jinfang (郝景芳) – winning the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel (The Three Body Problem 三体) and the 2016 Hugo Award for Best Novelette (Folding Beijing 北京折叠), both translated by Ken Liu.

Over the past three years I’ve scouted out and published many Science Fiction stories from around the world. Through the independent small press Future Fiction, I’ve published more than 60 stories translated from English, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Chinese. China has been particularly striking in recent years, with two authors – Liu Cixin (刘慈欣) and Hao Jinfang (郝景芳) – winning the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel (The Three Body Problem 三体) and the 2016 Hugo Award for Best Novelette (Folding Beijing 北京折叠), both translated by Ken Liu.

And yet, I would have never thought of being invited by Professor Wu Yan to the 4th International SF Convention in Chengdu for the promotion and advancement of Chinese SF, following the publication of Nebula, the first ever dual-language anthology of contemporary Chinese SF, published thanks to the contribution of the Confucius Institute in Milan, the Chinese company Storycom, and translations by Chiara Cigarini, Gabriella Goria and Alessandra Cristallini.

Of course the theme of multiculturalism in SF is rapidly growing in Europe and around the world (see the many panels during the last EuroCon in Barcelona and Dortmund and the recent WorldCon in Helsinki) and also in the United States, historically not inclined to publish stories from the rest of the world (see Rochester University’s study on the 3% problem), but things are changing.

Magazines such as Clarkesworld, Strange Horizons (and its sister magazine Samovar, with its dual-language SF), Apex Magazine, and Lightspeed publish authors from non-English-speaking countries and cultures almost every month. Not all these magazines translate the stories directly from the original language, waiting for the texts to be submitted already in English, but it is nevertheless a step forward towards the awareness that considering English as the only source of world SF is at least reductive, if not totally wrong.

In this context, finding out that China exports its authors abroad and is interested in World SF was a very pleasant surprise.

The 4th International Science Fiction Convention in Chengdu was held with the enthusiastic participation and support of local institutions and even the Chinese government, a sign that modernization and technological development, together with literature, are considered elements that bring social and cultural progress.

The 4th International Science Fiction Convention in Chengdu was held with the enthusiastic participation and support of local institutions and even the Chinese government, a sign that modernization and technological development, together with literature, are considered elements that bring social and cultural progress.

Never before, at any convention I’ve attended in more than 10 years (which was also confirmed by Neil Clarke, editor of Clarkesworld) has there been such an economic, academic and political support for a marginal - even if rapidly growing - phenomenon such as SF. Here are some excerpts from the speeches given during the opening ceremony by the Mayor of Chengdu, the provincial authorities, and the Head of Sichuan University:

“We want to turn China into a scientific power through imagination and innovation.”

“SF is the bridge between the present and the future of the country. And it serves the masses.”

“Imagination is the support to create knowledge, inspire people to transform their lives and generate scientific knowledge in the long term.”

“If young people are strong, society is strong.”

“How can we reduce anxiety about the future? Science fiction also serves this purpose.”

“We want to nurture science fiction in our country and thus contribute to the rejuvenation of society.”

Now, beyond the classic rhetoric of politicians, the entire conference was organized and funded by the Science Fiction World publishing house (owned by the Chinese government); all expenses were paid for the national and international guests, including Robert J. Sawyer and Derek Kunsken from Canada; Taiyo Fujii from Japan; Neil Clarke, Michael Swanwick and Crystal Huff from the United States; Nick Wells and Phoebe Griffin-Beale from the United Kingdom; and myself from Italy.

This kind of support has aroused great enthusiasm but also some legitimate reflections: What does the Chinese Government expect from SF? In what terms will it evaluate the investment it is making in this genre? And if things don’t go as planned, will it cut the funds to fuel the growth of this type of fiction, or will it accuse it of “spiritual pollution” as has happened in the past? And how much time will the government grant to writers and publishers to internationalize the SF industry, inside and outside of China? Perhaps the canonical five years?

I truly hope the support will last for a very long time, as the world really needs some literary balance in SF. And I am not talking in any way about politics: I am only referring to a simple principle of different points of view in order to maintain a wider market offer. I believe that nobody, especially those who promote the free market, would like to have a single worldwide SF supplier, otherwise known as the real monopoly.

The content offered at the convention was wide and diverse. The first panel was on “Science Fiction across National Borders,” in which I participated together with Crystal Huff, chair of conventions such as the Readercon in Boston and the latest WorldCon in Helsinki; Taiyo Fujii, one of the best Japanese SF writers; Li Keqin, editor of Science Fiction World; and Wu Yan, an expert in Chinese SF and recently appointed as Director of the “Center for Science and Human Imagination” at the Southern University of Technology in Shenzhen.

The panel began by highlighting some trends in SF, such as solarpunk, climate fiction and post-colonial fiction, and then it focused on the importance of preserving diversity in SF, especially because – apart from what happens in America and the UK – nobody really knows that much about what is happening in the rest of the world.

Also for this reason, much attention has been paid to China’s neighboring countries, such as South Korea and Japan, with specific panels on the national scene and future prospects. In May 2018, the first Asia Pacific SF Con will be organized in Beijing to coordinate the activities of the various countries with a view to greater collaboration and exchange between publishing houses, translators and authors, not forgetting other sectors such as audiovisuals and comics. Overall in 2016 in China, SF and its derivatives had an estimated market value of around one 10 billion yuan (around 1,5 billion dollars), as Prof. Wu Yan pointed out in his opening speech.

The Guests of Honor animated the scene with very interesting speeches such as Robert Sawyer’s on the possible relations between humanity and artificial intelligences. (Eventually, Sawyer predicted that a symbiotic relationship could be the best for everyone, human and otherwise, as we will both have to live on the same planet for quite a long time.) Michael Swanwick’s speech on how to build stories that no longer indulge in classic post-apocalyptic and dystopian visions, but on the contrary finally propose constructive solutions and approaches for a better future, was particularly appreciated.

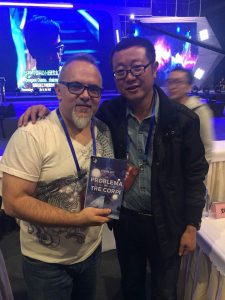

And then there were the Chinese writers, above all Liu Cixin who, with millions of copies of the Three Body trilogy sold in China and three hundred thousand in the rest of the world, attracted so much attention wherever he went, fans waiting for him with piles of books to sign. I had the pleasure of giving him his novel in Italian, translated by B. Tavani and published for Mondadori a few weeks ago (and had the book signed, it goes without saying...).

And then there were the Chinese writers, above all Liu Cixin who, with millions of copies of the Three Body trilogy sold in China and three hundred thousand in the rest of the world, attracted so much attention wherever he went, fans waiting for him with piles of books to sign. I had the pleasure of giving him his novel in Italian, translated by B. Tavani and published for Mondadori a few weeks ago (and had the book signed, it goes without saying...).

In addition to Liu Cixin, whose speech focused on the biological and mental transformations necessary for mankind to colonize space, there were many other writers and writers of unquestionable interest:

Han Song (韩松) – considered the Chinese Kafka mainly for the novel Subway (地铁) – works for the Xinhua news agency and he’s known to have said that he wrote more SF during the day as a journalist than at night as a writer. In his speech he talked about the history and importance of Science Fiction World magazine: back in the 1990s many of today’s Chinese entrepreneurs read SF, and SFW magazine played a key role in introducing new ideas to its readers and publishing stories of national and international writers in translation.

Xia Jia (夏笳), often translated in Clarkesworld and Future Fiction, is one of the most fascinating female voices because of her ability to combine Chinese tradition with technological developments in society, a sort of “porridge” SF, as her writing is defined, in which human emotions (respect for the elderly, love for children, sense of community) are rewritten in light of the boldest innovations in the fields of robotics, social networks, social engineering and virtual reality.

Chen Qiufan (陈秋帆), recently appointed president of the association of Chinese SF writers, represents the technological soul of the country. Working in the IT field and for digital companies, he’s interested in the drifts of progress and consumerism, intended as the blind acceleration and increasingly frenetic rhythms in order to achieve an endless growth toward the unknown. Beyond the idea of progress copied from the Western one, Chen Qiufan expresses all the doubts and perplexities inherent in the titanic enterprise of modernizing an immense nation in such a short time. His witty and discerning criticism has ensured him success and numerous translations abroad: his novel The Waste Tide (荒潮) tackles the problem of waste in consumer society and is soon to be published in the United States and Germany, translated by Ken Liu.

And then Zhang Ran and Bao Shu: the former has built his career on digital publications and has a huge base of followers online (as well as flesh-and-bone critics who appreciate his stories) while the latter has recently quit his previous work to devote himself to full-time SF writing.

The panel on the discovery of SF by the mainstream was a revelation. In China, a book like The Three Body Problem by Liu Cixin has divided public opinion. There were writers who appreciated it and those who criticised its language, considered too simple and not literary enough. Discussion between Xia Jia, Chen Qiufan, Fei Dao and Yun Chuanhong has also shown that many mainstream authors are approaching SF themes, while others claim the centrality of man rather than science. In the end, the fundamental question has remained unanswered: what determines the boundary between the “mainstream” and SF if both of them tend to get closer and overlap more often and with more success? Perhaps – and in the air there is a simple but difficult solution to accept – definitions don’t matter as much as the quality of literature.

Moreover, that SF is the best way to read contemporary China is not a new concept, but what is new is the interest that the mainstream is giving to a genre that has always been considered niche. (To my great surprise, subway riders looking at their smartphones were not playing but reading!). Furthermore, the number of skyscrapers is higher than any other nation, high-speed trains connect every remote corner of the country and apps of every kind (from reservations to transport and communication) have replaced offices- anyone who ignores or neglects this reality is destined to write for an elderly, culturally-backward, and rapidly-disappearing public. SF is therefore the fiction of the Chinese present, and the mainstream – albeit with reluctance – has understood this. The debate between critics and supporters of the genre has come alive and the two factions are divided on how much and what kind of credit should be given to SF.

The last panel in which I took part dealt with the issue of digital publishing in the age of mobile reading (although the book is already a mobile device). Nick Wells, UK publisher of Flame Tree Publishing, Phoebe Griffin-Beale of London’s SFX magazine and Tao Yunfei, an expert on digital platforms, discussed how to protect the intellectual property of works on new media in the light of some striking cases of plagiarism in China. Then, speaking of contents, the difference in the choices between large and small publishers emerged, where the former prefer popular themes that are appealing and easy to read, while the latter focus on scouting out what will become interesting, relying above all on the ability to intercept trends and recognize new voices. This mix of exploration and mass diffusion – if well built – might help to guarantee readers the widest and most varied possible range. Bit book industry and small presses are not opposed and can (and even more, must) cooperate in a culturally constructive way.

But the Chengdu convention didn’t end on Sunday afternoon. After the last panel, Robert Sawyer, Neil Clarke, Xia Jia, Zhang Ran, Bao Shu and I were invited to Sichuan University to speak in front of a few hundred students. Everyone – thanks to the excellent interpreter Emily Jin – had the opportunity to talk about their personal experiences as writers in relation to the common theme: “How did I learn not to worry and love SF.”

Everyone has shown in fact that every prejudice or apparent obstacle can be overcome if you really believe in your dream. Nobody, at the beginning of their career, had a clear path, nobody was sure to reach some goal, but the determination and a good dose of healthy and unshakeable madness allowed everyone to get here, in front of so many students full of enthusiasm and passion for SF. I am sure that at least one of these students will use this experience kickstart their own writing career.

A CULINARY NOTE...

Breakfast, lunch and dinner are such important events that they mark the rhythms of the day in an inexorable, or rather sacred way; a convivial ritual that must be lived together around a round (or square) table without a headpiece (a tradition that is being lost in modern restaurants). In addition, culinary habits (with the exception of breakfast, identical to lunch and dinner, a quite difficult thing for me) are similar to the Italian ones, and mostly in the South, in Chengdu, the cuisine resembles the traditional Roman one: intestines (such as pajata), gut (like trippa), various organs (such as kidneys, liver, spleen, tongue and brain). In addition, they have whole Peking ducks, which the chef serves by slicing them directly next to the table where you eat.

The “hot pot” is Sichuan’s specialty: in the centre of the table is placed a hot pot – divided into a normal and very hot section – where everyone cooks their own things among meat, fish and vegetables arriving in a continuous cycle during the course of one hour, if not more.

WHAT’S IN THE FUTURE?

On our last night in Beijing, in front of a beer and some dumplings with vinegar, one SF writer hinted to me about the next project of the Chinese government: “It’s pure science fiction,” he says while lighting a cigarette inside the restaurant because it’s late and nobody checks. “The Government wants to use Big Data to allocate each citizen the right share of resources according to income, actual consumption and social contribution. They want to realize the great socialist dream.”

I do not know if such a project will ever see the light of the day, but if it does, it can only happen in China, from which it is likely that a large part of the future awaiting all humanity will come. For this reason, given the technological acceleration and the socio-economic fragmentation, I am increasingly convinced that SF is the user’s manual for understanding the present and preparing ourselves for the future.

[…] L’anno scorso sono stato invitato alla Quarta Convention Internazionale di SF a Chengdu (qui il report) organizzata da Science Fiction World, storica casa editrice cinese di libri e riviste di genere […]

[…] is an important step. Last year I was invited to the 4th International SF Convention in Chengdu (here’s the report on Samovar) organized by Science Fiction World, historical Chinese publishing house of SF books and […]