Francesco Verso is an Italian author and publisher. The story “A Day to Remember/ Un giorno da ricordare”, by Clelia Farris, published in this issue of Samovar and translated by Rachel Cordasco, was first published in Italian by Francesco through his project Future Fiction. Recently he has published a dual Italian-Chinese language anthology of Chinese SF, Nebula. A review of his novel of his novel Nexhuman was published in Strange Horizons. We’re delighted that Francesco has taken time out of his busy schedule to answer some of our questions! You can also read his report of the recent international SF convention in Chengdu here.

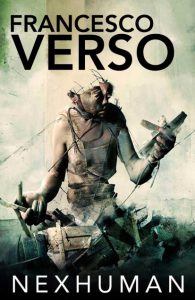

Your novel Nexhuman has been translated into English by Sally McCorry, and was recently acquired by Apex Publishing for US release. Can you tell us what inspired the book?

Your novel Nexhuman has been translated into English by Sally McCorry, and was recently acquired by Apex Publishing for US release. Can you tell us what inspired the book?

The main idea of book was inspired by something I saw some years ago: I in a flea market in Rome with my wife when we noticed—inside a big garbage bin—an 8 year old boy who had just found a doll as tall as him; he was cleaning it and caressing it as if it was his girlfriend. Then his mother came along telling him to move along and not to waste any time with the doll, as he should have been searching for more valuable things. This image, touching and terrible at the same time, started Peter Payne’s story and his seemingly impossible love. It is no secret that hyper-consumerism and overproduction is leaving on the ground of every city the price we have to pay for our neglect and lack of respect for the environment. In Nexhuman I've pushed this alarming situation to the extreme consequences of a process that is already visible almost everywhere.

How was the experience of being translated? Did you work with Sally McCorry as she was doing the translation?

It was a very hard bet: back in 2012, when Livido (Nexhuman’s original Italian title) won all the major Italian SF awards, I didn’t know how to submit the story to a publisher outside of Italy. I knew that nobody was waiting for an Italian SF book, as there hasn’t been one published in maybe more than 20 years and the 3% problem issue was a barely impossible obstacle to overcome. But I believed so much in the novel that I was determined to find an English speaking translator to help me translate Nexhuman. Meeting Sally McCorry changed everything: not only did she like SF, but she liked also the book and she had some spare time to dedicate to translating non-commercial fiction. So I invested my personal money, paying her her in 5-6 instalments as the work progressed, and we worked—chapter by chapter—to revise the text in order to come up with a good first draft. It took us around 1 year to complete the task, as we were both working on many other things, but finally I had my first English translation ready and I started to look for a place to submit it. The book was first published in Australia by Xoum in 2015 and the editor, David Henley, had another round of editing to finally polish and adapt the text for English readers. And then last summer, when Rachel Cordasco helped me submit the book to Jason Sizemore, something incredible happened. In just 4-5 weeks time after the submission, I received a publishing contract by Apex Books. This is the first Italian SF book to be published in the USA in a very long time.

This is just to say how incredibly difficult and unfavourable it is to be an SF writer born in a non-English speaking country. It takes so much more time and effort, just to compete with a book written in English.

Can you tell us about the current Italian SF/F publishing scene? Are there any particular trends that you're seeing?

Digital publishing and the rise of small presses have given new energy to Italian SF in recent years. Time travel (namely the long-standing Italian affection for the past, whether it’s the Roman Empire, the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, which is still generating many uchronias) and post-apocalyptic dystopias are two major trends in Italian SF books. Up to some years ago Italy might have been considered as producing more “soft SF” than “hard SF”. Today, thanks to the access to information, the spread of the internet and a better knowledge of English, writers such as Giovanni De Matteo, Clelia Farris, Francesco Grasso, Alessandro Vietti and Nicoletta Vallorani—just to mention a few—are absolutely comparable in terms of themes and quality to any other country producing SF at a professional level. Personally I am very interested in the posthuman condition and the transition to a new society where A.I., 3D printing, and bio- and nanotech will have a definitive role in shaping the reality of the things to come.

Which Italian SF/F writers would you like to see translated into English?

Certainly the ones I’ve mentioned above, but I’d like to spend a few more words for Clelia Farris. She’s a long time author of SF and she writes with a mature, harsh, extremely evocative style. Most of all, her stories have nothing in common with English fiction and often deal with the loss and sense of guiltiness deriving from futuristic technologies that allow us to exploit the human condition or be exploited by it.

Her book La pesatura dell’anima (The Weight of the Soul) is set in an alternative Egypt, where the use of metals is prohibited by law, houses and furniture are derived from modified trees, and biotech animals serve as means of transport and communication. A fascinating landscape complicated by the fact that Clelia Farris uses a weird language capable of creating a real sense of estrangement by adapting local slang and neologisms which are not easy to translate. I am very happy to announce that we’re working together with Bill Campbell, editor of Rosarium Publishing, and Rachel Cordasco to translate her first short story collection. Hopefully the book—whose draft title is Creative Surgery—will be out in 2019 in the USA.

Can you tell us a bit about the Future Fiction project?

It all started some five, six years ago because, as a reader, I was tired of going to Italian bookstores and finding always (or mostly) the same kind of story, written by the same kind of writer: namely a middle-class, English-speaking, white man or woman. I was missing a huge part of the representativeness of the real world, some kind of “literary biodiversity” which in other genres apart from SF—as paradoxically as it might seems—is not so extreme.

On Future Fiction I tend to publish stories preferably set on a near-future Earth, stories that face the coming issues of climate change, the new media sphere, artificial intelligence, the ethics of cloning and bio-engineering, the rise of nanotechnology, the latest applications of the 3D printing bottom-up revolution (from the future of food to nanomedicine and stem cells) and in general all aspects that will contribute to shape up the coming era; all concepts, thus, with a scientific and social value, as well as an anthropological and therefore human value.

Recently the project has developed more as a cultural small press than a commercial publishing house and after four years—during which I’ve published more than 60 stories in ebook form (of which 30 are in English) and 8 paperbacks—I’ve realized that I was looking for the missing voices of the “Science Fiction Hidden World”. Some might indeed define it as “diversity” (a term that is increasingly becoming popular in and out of the genre), but then I thought, “diverse from whom?” and again I was back to the original bias towards English-speaking culture. So now I call it “Science Fiction Fair Distribution”; just as the Seed Vault in the Svalbard Islands preserves biodiversity from a possible environmental apocalypse, I’ve set myself on a quest to preserve Science-Fiction-Literary-Diversity from a possible cultural catastrophe. What would the World (and its literary future) be, if there was just one language in which to talk about it, one religion, one culture, one economy and one single lifestyle to represent it?

You've been doing a lot of work recently with Chinese SF, and have just attended the 4th International Science Fiction Conference in Chengdu. What got you interested in Chinese SF, and what sort of things have you been working on? Can you tell us anything about the conference?

Looking at world SF led me to the growing phenomenon of Chinese SF. I believe that if we want to keep the genre alive and fresh we should not be scared of embracing new trends and cultures (even though China is not new at all and just like Italy has two thousand years of literature and traditions to derive its stories from). At this time, China is experimenting with a kind of SF world, a post-cyberpunk scenario where—on a monthly basis—technology and innovations are reshaping every aspect of society, from solar cells industrial plants to high speed trains (the so called Silk Road project to link Asia with Europe), and top universities forging the engineers, designers and visionaries of the next years.

In this context, the 4th International SF Conference in Chengdu was held in an atmosphere of great participation and support from the local institutions and even the Chinese government, a sign that modernization and technological development together with literature, are considered key elements to spread social and cultural progress.

Never before, in any convention I’ve attended to in more than 10 years (a fact confirmed also by Neil Clarke, editor of Clarkesworld) have I seen such economic, academic and political support for Science Fiction. There were panels about SF trends which are becoming more and more relevant, like solarpunk, climate-fiction and post-colonial SF, and others which focused on the importance of preserving diversity in SF, mostly because—apart from what happens in America and the UK—nobody there really knew much about what was happening in SF in the rest of the world.

And then there were the Chinese SF writers; above all, the best-selling author Liu Cixin, the cross-genre “Chinese Kafka” Han Song and the highly influential Wang Jinkang (the three of them are considered the “Three Generals” of Chinese SF) and then the new writers—the so called post-80s generation—like Xia Jia and her “porridge SF”, excellent hard SF writer Chen Qiufan, and the highly praised Zhang Ran and Bao Shu, who has recently quit his job to be a full time writer.

If you want to know more about it, I’ve written a full report on the Convention here.

And finally, can you tell us anything about your current writing project(s)?

First of all, let me thank you for the attention you’ve reserved for a small independent press like Future Fiction; I’d really like to invite all SF readers to explore—at least every once in a while—what’s behind the big, shiny billboards of big industry titles. I’ve done it myself and I’ve found there are a lot of wonderful, refreshing stories coming from unexpected sources. After all, isn’t that what SF is all about?

Regarding my current projects, thanks to Bill Campbell, editor of Rosarium Publishing, a Future Fiction anthology called “New Dimensions in International Science Fiction” will be out on the US market in March 2018 with a selection of stories written by the best contemporary authors coming from around the world.

On my personal writing side, my fifth book will consist of two volumes and it will be called The Walkers. The main theme revolves around this question: what would happen if a small part of Rome’s population stopped eating, gave up their jobs and left the city? The plot follows the life of a group of rebels, the “Pulldogs” (which gives the title of the first book), at the twilight of Western civilisation, who undergo an anthropological transformation caused by the dissemination of nanites (nano-robots capable of assembling molecules to create matter). This technology changes the way they feed themselves and gives rise to a culture which, while in some aspects reminiscent of an ancient nomadic society, is creative and new, based on 3D printing, artificial photosynthesis and mesh networking. The first book will be out in Italian next year on Future Fiction and it has already been translated in English by Jennifer Delare, while the second one, called “No/Mad/Land”, will be finished in 2018.

Thank you, Francesco!

Congratulations to you and your team, Francesco Verso: keep up the good work! As a translator I know only too well how difficult it is for talented Italian authors to crack the anglo market. Yet I see encouraging signs of an opening towards voices of different cultures and firmly believe that the future will see SF from all over the world translated into English.

[…] drive to write this story came from my editor, Francesco Verso, who asked me for a story about climate change. Cagliari, my city, reaches out to the sea, but it's […]

[…] bella intervista Francesco Verso su Samovar, che testimonia l’ormai salda presa di Francesco sui territori esteri. Un estratto (in […]