Translated from Spanish by the author, Andrea Chapela.

I don´t think the time is quite right, but it’s close.

I´m afraid, unfortunately, that I’m

in the last generation to die.

─Gerald Sussman

I haven’t even taken off my heels when my mother’s call comes in. I wonder if I should answer. The door hasn’t closed yet, and Gary is still reporting the house conditions: no milk in the fridge, some apples about to rot, window set to manual, heat turned off. I just want to take a bath, get into bed, and forget how hard it is to open a new greenhouse in the city. I lean against the wall, which is cold against my back. I let out a breath while the notification blinks in the upper corner of my sitefield. I could ignore the call and ask Gary to heat the water.

But I should really answer. Mom has called three times already, and she hasn’t left a single message. It isn’t like her. She always calls the second she needs something, and she always leaves a message. The red dot disappears—I changed its color years ago so I could tell her apart from other callers—and for a moment I breathe easier. I could just disconnect my com-channels and ignore the outside world. I could, but I don’t.

I slide down the wall until I’m sitting on the cold floor and kick off my shoes. They hit the opposite wall, and then I return the call. Mom answers immediately, and the space around me changes. The white walls and wooden floors of the apartment disappear. My lenses darken and with one blink I’m in the callroom that we designed together many years ago. The space looks like the living room of the house I grew up in, with its red carpet and wooden furniture arranged in front of an old LCD screen. Mom likes callrooms to simulate real spaces. Imagined settings, or the default white background that some people use, make her uncomfortable. The idea of sharing a personal image when talking to a stranger seems odd to me, but I don’t tell her that.

I blink to adjust my eyes to the space; in front of me is the sofa, where Mom usually sits with a cup of hot tea. In her place there’s a blurred shape, a white column of light flickering as if there’s a glitch. Is this an error?

“Is everything okay? Mom?”

“Greetings. This is a prerecorded message for recipient Anabel Orozco. Patient number 34H578-B, name Magdalena Orozco, is currently in intensive care. You have been named her emergency contact. Your immediate presence is required. The address is …”

The column of light gives me an address for a hospital in CDMX. It flickers, then repeats the information. I clench and unclench my fists in order to exit the callroom quickly. I’m in the apartment again. I’m shaking. It’s the cold, I think, before asking Gary to buy me a ticket to Mexico. It’s just the cold.

Later I find out that the hospital hacked Mom’s lenses to get an emergency contact because there wasn’t one on file. Her file was empty.

I was fifteen years old when Mom bought her first pair of SmartLenses. She got the year’s newest model. They came in a little yellow box. I was amazed at how they looked just like normal contact lenses at first glance, small and flexible, without any of stiffness or the bluish neuropigmentation of older models. It only took her a little practice to put them in. I was so jealous. I’d been using my own for at least two years. It had been a pain to get used to the itch but I could no longer imagine a world without them. Who needed screens, smartwalls, or phones when everything could open before your eyes like 3D?

Of course Mom didn’t see it that way. At first, she complained about the distractions. New windows were constantly popping up in front of her eyes, advertising this or that product. If she searched for a pair of pants, images would immediately pop up in the ad-board, the same pants on sale in other stores. She felt bombarded. Not to mention the kinetics.

“I never realized until now how much I spoke with my hands. I’m talking with the neighbor and suddenly I can’t see her and I’m somewhere else or I’ve called the grocery store …”

“It’s only movements up here,” I said for the fourth time, gesturing around my torso. “Mom, look at me. Movements up here are the default, but you can change it. We can set it higher so you don’t have to tap; you just have to think about it, and done. Lenses react to kinetic, voice, and thought instructions, remember?”

Back then we still lived in the old apartment in Colonia del Valle. Smart buildings had just started to pop up around the city in areas like Santa Fé and Polanco. We were sitting in the kitchen—which didn’t have any digitelligent features—and I’d shut down my coms so I wouldn’t get distracted. I was looking at a mirror image of what my mother saw on a spare tablet. She looked at me, and to see myself through her eyes was dizzying.

“I’m changing your lenses so you won’t see any of this. Just the basics,” I said, starting to adjust the settings. Mom kept insisting that I talk her through it, but I knew that it would take too much time to explain it.

“Just don’t touch anything. Mom, stop moving your eyes, you’re going to make me sick.”

“What am I supposed to do in the meantime?”

“I don’t know. Just hold still. It’ll just take a second.”

I adjusted the reaction speed, the sensitivity, even the scale of her sitefield. Basic configurations. Really, she would only use the lenses to make calls and search the web. She wouldn’t explore, watch concerts in 3D immersion, or participate in long-distance meetings. When I finished and rebooted the system, she let out a gasp of surprise when her sitefield went dark.

“It’s like going blind,” she said once she was able to see again.

“Now concentrate. Try to open your mail. Tell it to open up.”

“Open mail.”

“No, Mom,” I said, closing it again. “In your head. You don’t want to be like those people who can’t control their thoughts and have to say everything out loud, right? Do it again.”

“Ani, I’m not stupid. Just slow down.”

There were a lot of other things I could have been doing, but instead I kept helping her, like I’d help her with every future update, with the creation of callrooms, with the configuration of her house and health sensors. But I never thought of creating a back door to her lenses. It never occurred to me to supervise her. That’s something parents do, not children.

I try to find out what happened to my mother before getting on the Hyper, which Gary has decided will be faster even if it is more expensive than taking a plane. I call the hospital, but I only get an automated response, and I don’t feel like struggling through the recorded menus. I call Mom again, but get the same message. Finally, I try doña Carmela. After I left CDMX and Mom moved into a smaller place, doña Carmela was her neighbor in the apartment across the hall. That was fifteen years ago, and doña Carmela hasn’t changed a bit. She keeps tabs on everything that’s going on in the building. I can always tell that Mom is parroting doña Carmela if she told me the woman in 15-D, who, rumor has it, is addicted to long-distance dating, or about the young couple in 26-B, who always leave their windows open as if they want the whole block to hear them. Doña Carmela answers immediately.

My mother has been going out less and less in the last two months, she says. Doña Carmela only saw her at the tenant meetings on Mondays. But two weeks ago, Mom fell down the stairs. She was on her way to buy milk, but after falling she returned home, said she was alright, and refused to see a doctor. Doña Carmela assumed it had been only a stumble, nothing serious. But this morning, while they were talking, Mom passed out.

“Right in front of my very eyes, mija. She fell straight to the floor and I couldn’t wake her up. I immediately called the ambulance. Do you know how she’s doing?”

I tell her that I don’t know, but I promise to contact her once I find anything out, and then I board the Hyper. When I take my seat, I shut down my coms; one thought is enough to make all the windows disappear from my sitefield. I settle into my seat and close my eyes. I’ve never liked the sensation of speed in the Hyper. I take a deep breath just before the pull.

While stuck in CDMX’s traffic, I’m finally able to talk to my mother’s doctor at the hospital.

“The damage from the fall has been repaired, nothing a nanometric regeneration would not fix, but the general asthenia is of greater concern. There is no record to indicate the patient has been self-monitoring in the last few months. Her records are inaccessible and her sensors appear to be turned off. Already some of her internal organs have been compromised due to transmodifications. They need to be replaced, but she is refusing treatment. I see here that she was operated on last year.”

What the doctor said was true. That was the last time I saw her in person. I’ve been too busy. We talk every week in the callroom, and it feels like I’m right there with her.

“Is she awake?”

“Yes. She woke up one hour ago. She has been informed that you are on your way and that she is in no state to make decisions concerning her health. The hospital would rather wait for you. The patient is communicating normally, but her brain activity levels indicate she is not fully conscious. She needs to be treated.”

“I have to choose?”

“According to hospital protocol, yes. You are her closest relative.”

I end the call. I hate talking to robots and my decision to take a taxi from the station, thinking it would be the fastest option, seems to have backfired. I’m stuck on Viaducto. Maybe the Metro would’ve been a better idea, but nothing works in the city on rainy days. Traffic is worse than ever. It’ll take me an hour to get to the hospital, something unimaginable in a fully digitelligent city, where everything is programmed to work in sync. But CDMX is stuck between the future and the present. The streets have been adapted to fit the new superconducting transport and driverless cars, but the evening rain still makes life difficult. I don’t even know if the connection will work for the entire ride, so while the data is up I tell Gary to message Abby and my boss.

I let them know where I am, what’s going on, that I’m okay, but I don’t say that Mom is waiting in the hospital, needs an operation, and that the decision is up to me. I don’t say it because I already know exactly what I have to do.

The last time I saw my mom in person was in the spring. During a routine exam, they discovered that her bladder was enlarged. It was an uncontrollable transmodification that Mom had let grow after ignoring her sensor’s alerts. After the diagnosis, I traveled to CDMX to keep her company for the appointments and the operation.

The procedure went well, and after two days Mom was sent home to rest. She was strong and getting better every day. She’d been saying that she wanted to travel again. But she wouldn’t; we both knew it. Two years before, she’d travelled to Europe, but had suffered a panic attack that sent her back home two weeks early. The spreading digitelligence combined with the unknown didn’t thrill her; they overwhelmed her. But in spite of the panic and the operation, at ninety-seven, she still seemed full of plans.

“I was thinking the other day that when I was born, life expectancy was ninety, and a person couldn’t live past a hundred and twenty,” she told me with ease, as if she was talking about the weather. I was going back to New York the next day, and we were cooking dinner without robotic arms, just like we used to do when I was little. “But here I am, with a new bladder at ninety-seven, twenty years older than my mother when she died, and everything seems fine.”

“Is that what you’ve been thinking about?”

I hardly ever thought about age; at forty-three, I was still young. My sensors detected any sign of disease years before it took hold and, even if preventative treatments didn’t work, like in Mom’s case, organs could always be replaced.

“This thing inside me …”

“It’s just a new organ, Mom, not a thing.”

“I was thinking about how unnatural it is, that you get sick and the solution is to change out body parts like you change socks. So what if I have deformities? I’ve lived ninety-seven years—of course I’ll have some deformities. Sometimes I see pictures of my mother and I think about how my own skin isn’t wrinkled or stained at all. Then I remember how she looked before she died and I think, how natural is all of this, really?”

“It’s natural now, Mom. When Grandma was alive, people still aged.”

“People are still aging, Ani. I’ve been thinking about it since the hospital. I don’t know if I want them to dismantle me little by little. I don’t know if I want to die as an assortment of organs and skin that were never mine to begin with. Maybe I want to die in this body, with this skin, in this house, with dignity. You know what I mean? Not with my body opened up in a hospital bed.”

I put down the knife. The kitchen suddenly felt too warm. The last thing I wanted to talk about was her death.

“Mom, come on, it was only a little scare. If you take care of yourself, you could live many more years. Life is so long now.”

“But that’s the problem. Life seems so long now, but, really, life always seems long when you’re young and short once you’ve lived it. There should be a time when we stop, a time when we decide enough is enough.”

I took a breath. “Well, you don’t have to decide that right now.”

“I just wanted to let you know how I feel. I’ve been thinking about it, and I’m serious. When the day comes when the only options are to replace my whole body or let me go … I want you to let me go in this body, here, in this apartment. You don’t have to watch, but I want you to give me that.”

At first I said no. She was thinking too far ahead, she still had many years to live; she shouldn’t be thinking like this, like an old lady. But in the end I said yes, I told her that I’d do whatever she wanted.

I never thought the time would come so soon.

I get to the hospital around midnight. I fill out all the forms, signing off on the consequences of our decision. The doctor informs me about her delicate condition, how nowadays there are procedures that can guarantee her improvement—she could live ten, twenty more years. But what I´m choosing won’t give her any time at all.

At this moment, in the small office, I’d rather have a human doctor and not a robotic one, full of facts and nothing else. Its body looks human to comfort patients, but its gestures are minimal, its eyes fixed, its breath nonexistent. Right now I’d prefer that the one telling me I’m condemning Mom to her death were at least breathing. I don’t want to be told that I’m choosing for her to die—she’s the one doing the choosing, I’m just the one signing the papers. I’d like to explain to the doctor that Mom doesn’t want her organs replaced, she doesn’t want to be reduced to bits and pieces, to be regenerated over and over again. She wants to die in the body she was born with, she wants to die with dignity in her own bed, away from the hospital. But it seems artificial doctors can’t understand this, they aren’t programmed to understand that someone might choose to die. They are programmed to cure, to preserve life. Not to comfort relatives.

The doctor shows me my mother’s file. There’s no information in the last couple of months. I recognize the date. The same day I left for New York she turned off her sensors and disconnected her home from the web. She’d already decided what she wanted before she fell. The transmodifications could have begun at any moment in the last few months, spreading quietly, without warning. But I’m not deciding anything. Mom chose this a year ago, Mom knew the consequences, Mom …

When I finally see her, I know that all the calls in the last few months have been nothing but lies. How hadn’t I noticed that she looked so small, that her hands didn’t stop shaking, that almost all her hair had fallen out, that her skin seemed too big for her body? I’d forgotten—or maybe I didn’t want to remember—that in a callroom what you see isn’t reality, but memory. I can’t believe that this woman sitting in the wheelchair in hospital pajamas and a robe is my mother. She returns my hug, but it’s the ghost of a hug, just her arms on my back, weightless. When she talks, I recognize her voice. She’s my mother, I know, but how long has she looked like this?

I thank the doctor and then push the wheelchair toward a taxi that will take us to her apartment. On the way, she rests her head on my shoulder and closes her eyes. She tells me about the hospital food, the doctors that kept insisting she have the operation, and how happy she is that I’m here. I can’t stop wondering how a human being can exist weightlessly. She feels so light, so cold. If someone told me she was made of air, I’d believe them.

She hugs me, and I’m no longer sure who is holding whom. If I close my eyes, I’m a little girl again. I try not to think about how small she feels, how her bones feel exposed under her clothes, how she gently trembles under all those layers. But she strokes my hair like I’m the sick one.

I want to ask her if she’s sure, but I don’t know how to say it without sounding like I’m begging her to change her mind. Before I find the right words, she sighs and her voice comes out weak, as if someone had turned down the volume:

“Thank you, Ani.”

I don’t know if she’s thanking me because I’m here or because I’m respecting her wishes. I don’t answer. I’d like to cry and have her comfort me, but I don’t. Crying over Mom’s death while she’s still alive, while she’s holding me in her arms, just doesn’t seem right.

But later, when she’s asleep, I lock myself in the bathroom, sit on the floor between the shower and the toilet, and allow myself to cry. I allow myself to admit I have no idea what’s right.

“Explain to me what a callroom is.”

Mom was spending a few weeks in New York with me. I’d moved to the city five years before, and it excited me to show her around once I finally felt at home. Back then I lived in a digitelligent apartment the size of a shoe box. I wouldn’t meet Abby until months later, and I wouldn’t move into her apartment until several years after that. Mom would never see it. She’d only visit that tiny space, where Gary—I’d finally saved enough to get an AI of my own—had shrank the bathroom, compressed the kitchen into the wall, made the bedroom bigger so two beds could fit.

That small space was mine alone and with the range of new intelligent modifiable materials, Mom and I could sit on a balcony that took up over half of the apartment’s space. We were drinking gin and tonics, the robotic arm in the kitchen had made them for us, to celebrate that it was almost summer. But Mom had barely drunk from hers. She was more interested in talking about callrooms, as if they were something new, and not an old technology.

“Instead of talking with projections or videos,” I told her “you design a shared callroom. It’s like a 3D simulation in your sitefield. The callers can choose how it looks. It feels like being in the same room with them. It’s almost like being there, you just can’t touch each other.”

“You and I should have one. You’ve visited so few times and you’re always busy. I know work’s important, and you’re just starting, and you’ve got such little vacation time, I know. But doña Carmela won’t stop telling me how real they look.”

“Well, they do. It’s a mix of immersion and old screen calls. Years ago the ad said that it was the closest we can get to teleportation.”

Mom smiled and drank a little bit. Maybe she didn’t like it, maybe I should order Gary to mix something else.

“I’ve been thinking how ours could look.”

“Retirement has left you with lots of time,” I said before asking her to continue.

She knew by heart the room’s measurements. She wanted a red rug, bright red like it was in the old apartment when it was really new and it didn’t have any stains. The same four dark leather chairs she had inherited from her mother. The light wood coffee table that matched the other two tables near the sofas. Everything arranged towards the television set.

“We don’t need an old television. We could put in some windows. Or just light. Or maybe some landscape. Some old European countryside.”

“No, no. I want that living room. With its white walls and its big windows to the side and the old television that we never turned on. I want it all the exact way it was when I moved there with you.”

The ice in my drink had melted and the afternoon heat was stifling. It felt as if my body had melted into the chair. We could start talking about dinner, maybe go out somewhere. We could leave the callroom for later.

“Why that living room? You sold all the furniture when you moved out.”

“I sold it because they were old. But it was the first safe place for you and me. My mother’s furniture, the old apartment. I’d like to meet you there.”

That night, when Mom was asleep, I sat down at a table where the kitchen was sometimes and I designed the callroom. The next morning we tried it together, I outside the apartment, and Mom inside it. In the blink of an eye we were face to face in the living room of my childhood. Mom tried to hug me before she remembered that it was the only thing she couldn’t do.

“It’s amazing. It’s like being there again.”

When we get to the apartment, Mom asks me not to turn on the data. She says that months ago she decided to stop living surrounded by that noise, that she only uses it to talk to me. She says that she couldn’t focus on the lenses anymore and started to use a screen. She reserved the lenses for our weekend chat, but she’s still wearing them.

I deactivate Gary and when I walk into the apartment I resist the urge to get onto the system to open the windows or turn on the lights. I only do this briefly over the next few days, when I have to modify the rooms to meet Mom’s needs. I transform the sofa in the study into a bed, I put handles on the bathroom wall so that Mom can go to the toilet alone, until she doesn’t even have enough strength for that and I have to start helping her.

When I talk to Abby, she tells me to bring Mom to New York with me. She says that she can get her treatment from better doctors with less invasive procedures. I could go back to work, I wouldn’t have to use up all my vacation days. I say no because I know that Mom doesn’t want to get shots, to be opened and closed for months, having her organs changed one by one, her blood cleansed by the liter, spending her time connected to a machine until her body decides that it can’t take anymore.

She quickly grows weak in front of me, as if the moment she left the hospital—choosing a death with dignity—whatever was holding her body together, keeping her alive, started to fall apart. I’ve heard her repeating the same phrase, “to die with dignity”, again and again since I got here, but I still don’t understand the meaning. What dignity is there in choosing to die? To not fight? What is the dignity of dying in bed? I ask myself those questions when I’m helping her go to the bathroom, when I’m making her food, when I’m reading to her, when I listen to her sleeping.

This, this progressive weakening, it’s what she wants. She wants to get smaller and smaller like she’s undergoing some kind of shrinking procedure. She says she’s cold, she’s hungry, she’s tired and sometimes I can’t tell anymore who’s the daughter and who’s the mother. But one morning, after breakfast, before I help her shower, I ask:

“Are you sure, Mom? You don’t want to come home with me?”

Mom cowers, as if the idea causes her physical pain, and then shakes her head. How can I let her choose right now? What she is doing, what I’m allowing her to do, is assisted suicide. She is sick in a time when sickness no longer exists, and she’s letting her own body rebel, spin out of control.

“Do you want to go to the salon?” she says to change the subject, without answering my question. “I’d like to get my nails done. My roots need a touch up, too.”

Her voice is a mere thread of what it was. I nod, and while she’s in the bathroom, I call the salon on the corner, where she’s gone for the last ten years, to make an appointment.

We spend the rest of the morning surrounded by the smell of acetone and the sound of neighborhood gossip. Mom is sitting under the salon’s yellow lights with her hair up and covered with purple mush, and when she laughs, her face—tired but happy—gets stuck in my brain, I tell myself to remember it. It’s the last time I hear her laugh. The last time she goes outside the apartment.

Last fall, Mom said she didn’t want to come to New York for Christmas. She said she understood that I couldn’t go to Mexico with work as busy as it was, but she didn’t want to fly. I said she could just take a Hyper, that it didn’t feel like flying, but she wouldn’t do that either.

“I don’t want you spending Christmas alone.”

“Doña Carmela invited me over. I won’t be alone.”

I wasn’t convinced. I often had the feeling that she wasn’t telling me the whole truth, that she was just telling me an edited version of what had happened to her. But how could I blame her for anything if I couldn’t even make time to spend Christmas with her?

“Are you sure everything is okay?”

“Everything is fine, Ani. I’m just tired. You know how winter is here. People go mad … I can’t even go to the movies, there isn’t a single self-car free in the whole city.”

For the first time I asked myself if maybe my mom’s head, not her body, would go first. Maybe despite all the medical improvements, even when the outside remains intact, there’s something inside humans that gets worn out, something still unidentified and incurable, something that is unable to contain all the time lived and when it overflows, living becomes unbearable.

Over the next few weeks I couldn’t focus on work even when I was really busy. I felt I should go and see Mom; something seemed wrong, but I’d just been promoted and was in charge of supervising a new greenhouse complex. I couldn’t leave. I needed to be in New York. Some things still need to be done face to face, people still need to be in front of a human being and not a machine when they sign papers or hand over big sums of money.

During our next call a week later, she sounded better. She told me about the movies she’d seen recently, about the people she’d met at the gym and about her new German classes, for when she felt like traveling again. I didn’t say that if she couldn’t take a Hyper to New York, she wouldn’t be able to go to Germany. I didn’t want to broach the subject again. When I saw Mom so tired, I felt afraid. I felt afraid thinking about the day when I would be the same.

The night Mom dies, we have dinner in bed together, which means that I sit by her and I encourage her to eat a spoonful of puree while my food cools on the desk. Mom rarely insists that we eat together, she’s so weak she has trouble staying upright. Sometimes I feel like she’s there, but she isn’t really, as if in front of me there’s only an empty body that sleeps, complains, and eats. Other times she takes my hand with impressive strength and makes me stay by her side longer, asks me to spend some more time with her, to read to her.

When she falls asleep, I turn off the light, go out carrying the dishes and leave the door to the study half-open. Mom has started snoring in the last week and the deep noise fills the apartment. In the beginning the sound made me hold my breath, I thought it might disappear at any moment, but now it’s become part of the house. I turn on a personal screen and put some classical music on. I work with headphones on for two hours, but I have the music low so I can still hear Mom above the sound of the piano.

When I get tired of working long distance—I need to look over a budget for errors so I can send it to my boss for his meeting tomorrow—I take my headphones off and make myself a cup of tea. I miss Gary at times, but for some things I don’t need him anymore. I don’t even know the last time I checked my own health.

While the water is on the stove, I go to the bathroom and look at myself in the mirror. I’m thin, paler than ever, and I have black bags under my eyes. Maybe Mom’s sickness has gotten inside me. I know it’s impossible, she’s suffering from old age. But who really gets old nowadays? Just my mom.

I go back into the kitchen. I pour the water in a mug and sit at the table to read. I had never been interested in books, but in the last few days I’ve developed the habit while reading out loud to Mom. I’ve started looking for answers in those books written a hundred, two hundred, three hundred years ago. I’m looking for ways to understand death, to understand how I’m supposed to feel about it, how to think about what is happening. Maybe it’s my fault. I’ve never thought much about death. When I was little, I wondered about it, but it always seemed so far away, so foreign, it wasn’t a real possibility.

In the past, when death happened more often, they must have known how to feel, how to face it. Did they talk about death? Were people better prepared? They should have been. When sickness was common, there were surely better ways to go through this than the wait and the stillness I’m feeling now. I open the book, but I can’t concentrate. Suddenly, the room is suddenly quiet. I hold my breath. I stay in the chair, waiting for the next snore. Silence grows around me.

Mom is dead.

I get up and leave the apartment. I can’t breathe. I inhale and exhale quickly, as if speed could stop the drowning. I close the door behind me. The noise it makes echoes in the night. Her body stays on the other side and I feel a new desperation in the pit of my stomach. In the hallway the window is open. The air smells like wet earth and sidewalk, it sounds like cars and street food vendors. Outside the world is alive. Inside is Mom. How can a door be the only thing separating these spaces? I close my eyes and try to go into our callroom.

Something stops me. It’s as if there is a barrier, a wall, or worse … as if the callroom never existed. I try again, verbalizing what I desire in my mind. Then I use a hand gesture. Finally I command the air:

“Call Mom.”

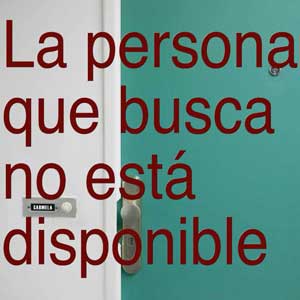

Again I feel a barrier and then a new message appears:

The person you are trying to reach is not available.

I look at the red letters, shining bright against doña Carmela’s door and the night. The callroom of my childhood, my Mom, are out of my reach. I shut down my lenses and the world fills with a new silence. In front of me all that is left is reality: the hallway of the apartment building, the open window, the night air.

This story was made possible by a generous Jóvenes Creadores grant, from Fondo Nacional de las Artes in Mexico, to Andrea Chapela.